Suppressing ion migration in metal halide perovskite via interstitial doping with a trace amount of multivalent cations

(2022) - Yepin Zhao, Ilhan Yavuz, Minhuan Wang, Marc H. Weber, Mingjie Xu, Joo-Hong Lee, Shaun Tan, Tianyi Huang, Dong Meng, Rui Wang, Jingjing Xue, Sung-Joon Lee, Sang-Hoon Bae, Anni Zhang, Seung-Gu Choi, Yanfeng Yin, Jin Liu, Tae-Hee Han, Yantao Shi, Hongru Ma, Wenxin Yang, Qiyu Xing, Yifan Zhou, Pengju Shi, Sisi Wang, Elizabeth Zhang, Jiming Bian, Xiaoqing Pan, Nam-Gyu Park, Jin-Wook Lee, Yang Yang

- Link:

- DOI: 10.1038/s41563-022-01390-3

- Zotero Link: Suppressing ion migration in metal halide perovskite via interstitial doping with a trace amount of multivalent cations

- Tags: #paper

- Cite Key: [@zhaoSuppressingIonMigration2022]

- Linked notes: Paper Annotations

Abstract

Cations with suitable sizes to occupy an interstitial site of perovskite crystals have been widely used to inhibit ion migration and promote the performance and stability of perovskite optoelectronics. However, such interstitial doping inevitably leads to lattice microstrain that impairs the long-range ordering and stability of the crystals, causing a sacrificial trade-off. Here, we unravel the evident influence of the valence states of the interstitial cations on their efficacy to suppress the ion migration. Incorporation of a trivalent neodymium cation (Nd3+) effectively mitigates the ion migration in the perovskite lattice with a reduced dosage (0.08%) compared to a widely used monovalent cation dopant (Na+, 0.45%). The photovoltaic performances and operational stability of the prototypical perovskite solar cells are enhanced with a trace amount of Nd3+ doping while minimizing the sacrificial trade-off.

Figures

Notes

Annotations (3/10/2023, 5:38:44 PM)

“Here, we unravel the evident influence of the valence states of the interstitial cations on their efficacy to suppress the ion migration.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1396)

“Incorporation of a trivalent neodymium cation (Nd3+) effectively mitigates the ion migration in the perovskite lattice with a reduced dosage (0.08%) compared to a widely used monovalent cation dopant (Na+, 0.45%). The photovoltaic performances and operational stability of the prototypical perovskite solar cells are enhanced with a trace amount of Nd3+ doping while minimizing the sacrificial trade-off.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1396) #nodes_research For stability improvement, they add (0.08%) Nd3+

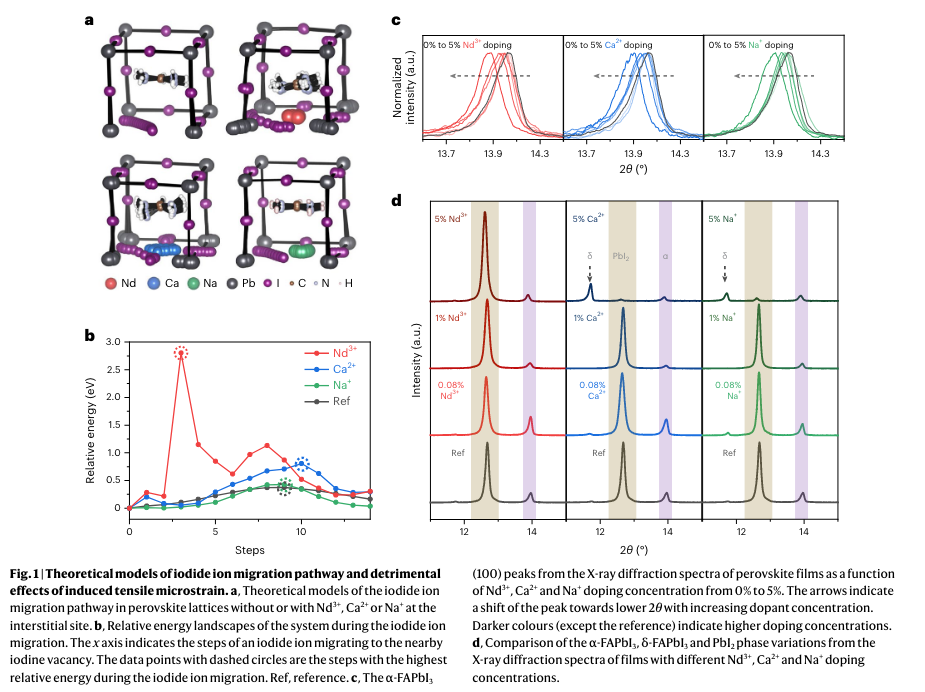

“as the dopant concentration reaches 1%, the intensity of the (001) α-FAPbI3 peak is reduced while that of the (001) PbI2 peak intensifies. A further increase in the dopant concentration to 5% induces the appearance of a (010) non-perovskite δ-FAPbI3 peak, indicating a destabilization of the α-FAPbI3 perovskite phase as the concentration of the interstitial dopants increases.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

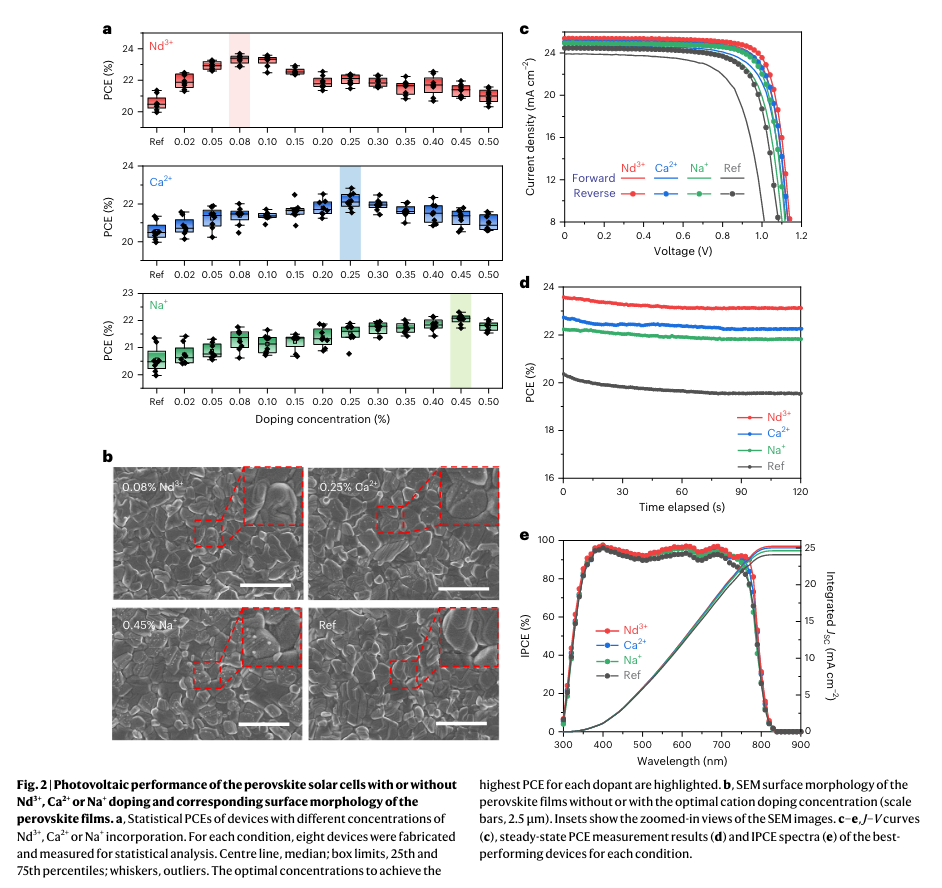

“Noticeably, the optimal doping concentrations for the highest PCE values were varied depending on the cations: 0.08%, 0.25% and 0.45% for Nd3+, Ca2+ and Na+, respectively. With 0.08% Nd3+ doping, a distinct enhancement in the average PCE was achieved from 20.56 ± 0.49% to 23.31 ± 0.29%, while 0.25% Ca2+ and 0.45% Na+ doping result in average PCEs of 22.07 ± 0.35% and 22.05 ± 0.19%, respectively. The open-circuit voltage (VOC), short-circuit current density (JSC) and fill factor (FF) values were largely improved by cation addition (Supplementary Figs. 11–13 and Supplementary Tables 4–6).” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

“While the overall grain sizes of the films are comparable, closer inspection of the images reveals that small particulates are segregated on the surface of the films with 0.25% Ca2+ and 0.45% Na+.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

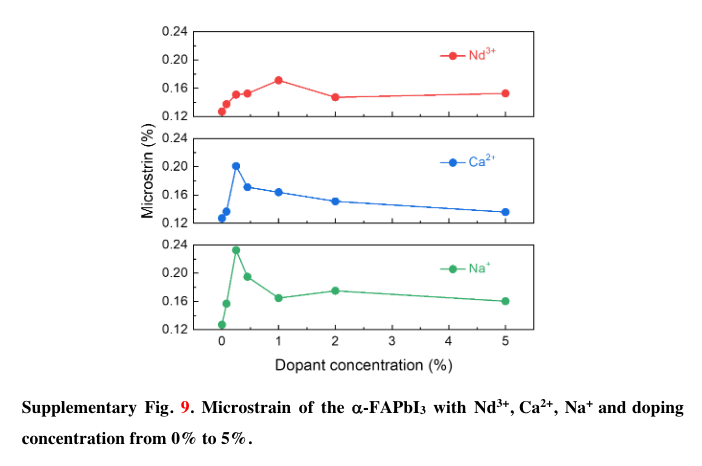

“We speculate that the relatively higher microstrain (>0.19%; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3) induced by 0.25% Ca2+ and 0.45% Na+ might cause clustering and segregation of the dopant on the crystal surface and/or grain boundary, which might limit performance enhancement by a sacrificial trade-off27. However, the film with 0.08% Nd3+ showed a neat surface, comparable to the reference film, and thus the side effects are probably minimized.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

“Negligible current–voltage hysteresis was observed for the device with the Nd3+ dopant, whereas the Ca2+ and Na+ dopants can only partially reduce the hysteresis observed from the reference device (Fig. 2c).” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

“nterstitial doping of alkali metal cations such as lithium (Li+), sodium (Na+), potassium (K+) or rubidium (Rb+) has been widely used to inhibit the migration of halide ions to relieve current–voltage hysteresis and improve operational stability15–17” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397) #nodes_research

what has been used for doping to suppress ion migration

“the interstitial doping can potentially distort the perovskite lattice and induce microstrain that undermines the long-range ordering and stability of the desired phase1,18,19.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397) #nodes_research doping can change the lattice, then induce strain that will decrease the stability in desired phase.

“we demonstrate an efficient interstitial doping strategy based on the trivalent neodymium cation (Nd3+) to appreciably prevent halide migration in the perovskite lattice with a minimal dose addition.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

“Compared with cations with similar ionic radii but lower valences, including calcium (Ca2+) and sodium (Na+) cations, the higher valence state of Nd3+ provides a better capability to obstruct halide migration and leads to an advantageous device performance by the perovskite solar cell with a substantially lower dopant concentration.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

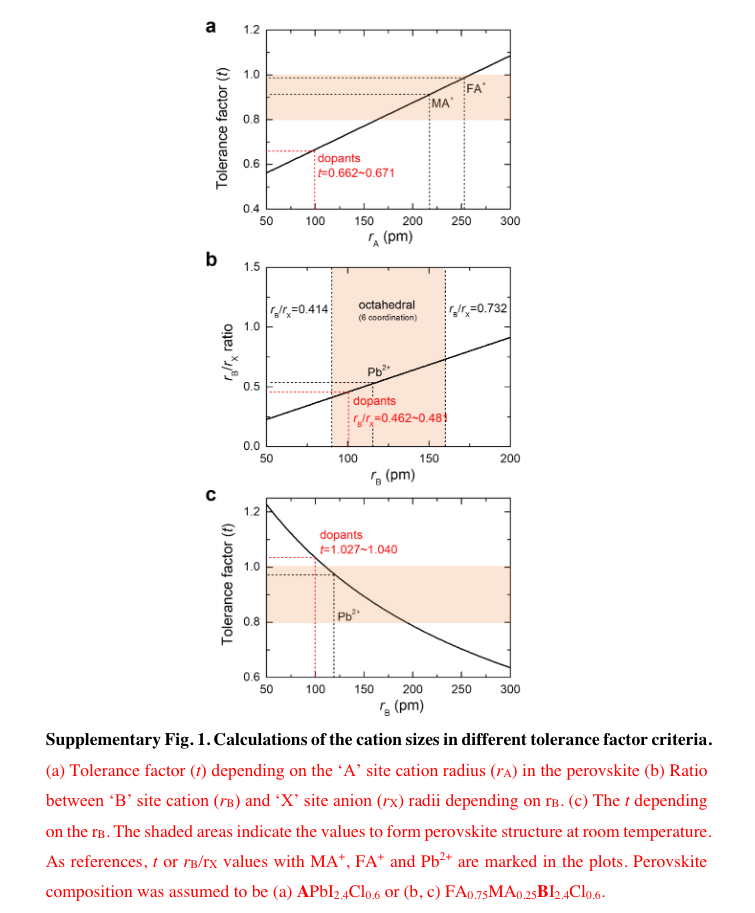

“The effective ionic radii of Na+, Ca2+ and Nd3+ are 102, 100 and 98.3 pm, respectively. Since their radii are much smaller than those of commonly used A' site cations such as CH3NH3+ (MA+, 217 pm) and HC(NH2)2+ (FA+, 253 pm), putting these cations into A' sites cannot satisfy the tolerance factor criteria (Supplementary Fig. 1a)20,21.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

“Without the interstitial cation, the energy barrier for the VI migration was only about 0.37 eV. The presence of Nd3+ enhances the energy barrier (2.80 eV), with lower enhancements for Ca2+ (0.81 eV) and Na+ (0.43 eV). Considering the similar sizes of the cations, the distinction of the ion migration impedance capability might be primarily related to the valence states of the cations. Nd3+ ions with three positive charges are more likely to restrict the motion of negative iodide ions due to a stronger electrostatic attraction force.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

“The progressive shift of the (100) orientation peak of α-FAPbI3 to a lower 2θ angle (where θ is the Bragg angle) with increasing cation dopant concentration is evidence of the interstitial incorporation of the cation and thus induced lattice volume expansion due to the tensile microstrain.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1397)

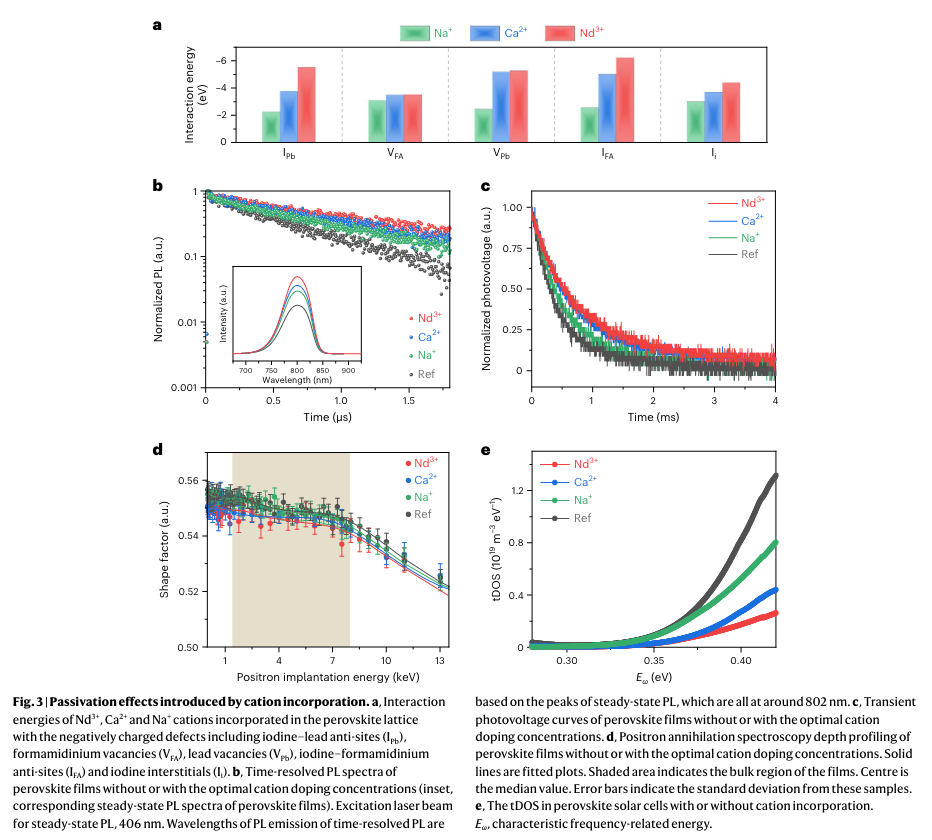

“We observed an elongation of the PL lifetime for the films with the three cations compared with the reference perovskite film; the PL lifetimes of the Nd3+ (1,340 ns), Ca2+ (960 ns) and Na+ (873 ns) films were longer than that of the reference sample (588 ns; Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 8)” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1398)

“ositron annihilation spectroscopy was employed to compare the density of negatively charged or neutral vacancy defects in the films (Supplementary Note 3). The positively charged positrons are implanted from the perovskite surface, and are annihilated upon interaction with electrons from a free lattice site or after trapping at negatively charged or neutral (but not positive) vacancy defects to emit two gamma photons30” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1398)

“y changing the kinetic energy of the incident positron, we were able to investigate the depth-dependent defect density of the films incorporated with different cations (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 23a)” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1399)

“The results show that the shape parameters of the films with the cation doping in the bulk (positron implantation energy from 1.5 keV to 8 keV; shaded region in Fig. 3d) are lower than that of the reference film, indicating a decreased density of negatively charged or neutral defects in the bulk region as a result of cation doping.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1399)

“We further cross-checked the trap density by measuring the trap density of states (tDOS) for the as-fabricated devices incorporated with different cations using angular-frequency-dependent capacitance measurement. As shown in Fig. 3e, the density of in-gap states for the devices with Nd3+, Ca2+ and Na+ dopants is decreased compared with the reference device, where the tendency in the measured trap density coincides with the PL and positron annihilation spectroscopy measurements (the density of in-gap states of the sample doped with Nd3+ is lower than that of the sample doped with Ca2+, and they are both lower than that of the sample doped with Na+).” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1399)

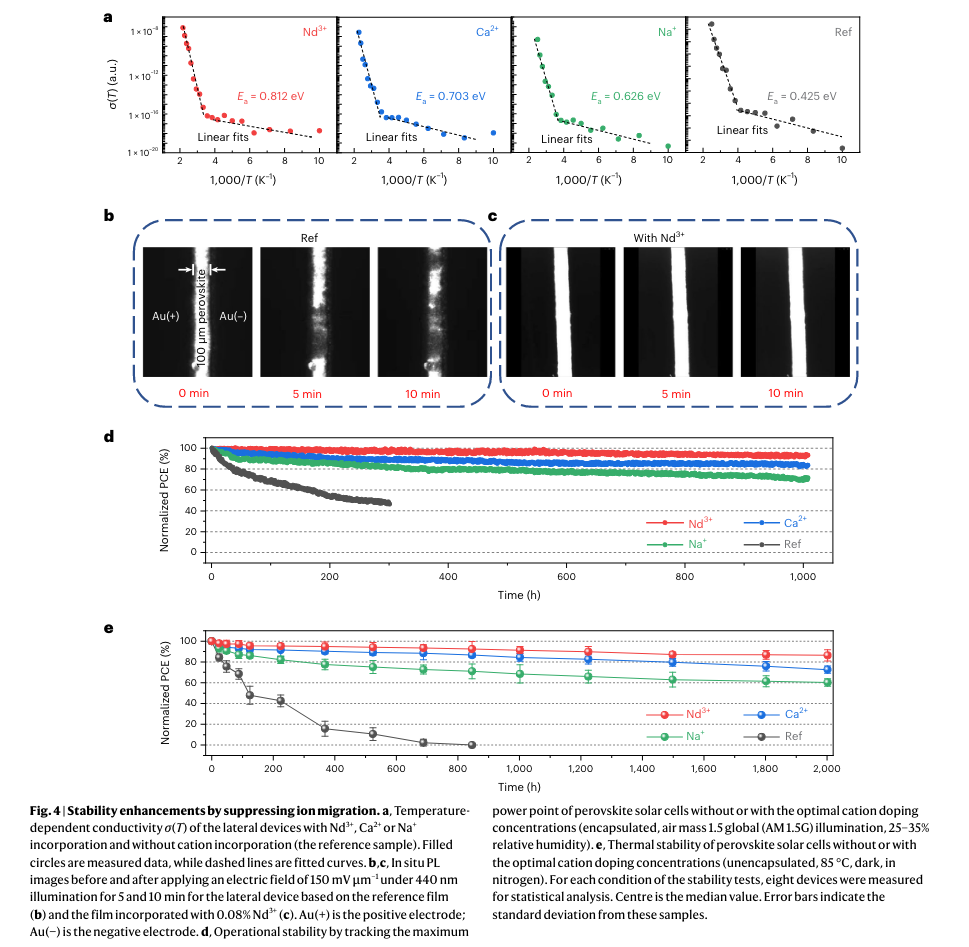

“To experimentally verify the effect of the different cation dopants on the ion migration energetics, we performed a temperature-dependent conductivity measurement on lateral perovskite devices with a structure of Au/perovskite (100 𝜇m)/Au.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1399)

“The activation energy (Ea) for ion” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1399)

“migration can be extracted by a linear fitting of the data based on the Nernst–Einstein equation, given by σ (T) = σ0 T exp( -Ea kBT ), where σ(T) is the conductivity as a function of temperature T, σ0 is a constant and kB is the Boltzmann constant12.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1400)

“The Ea value was extracted from the slope of the fitted lines at relatively higher temperatures (Fig. 4a). The calculated Ea values for the film incorporated with Nd3+, Ca2+ or Na+ were 0.812 eV, 0.703 eV and 0.626 eV, respectively, which are substantially higher than that of the reference film (0.425 eV). The trend of the measured Ea values also agrees well with the simulation results.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1400)

“he in situ PL measurement was performed using the lateral device under 440 nm illumination and an applied electric field of 150 mV 𝜇m–1 to visualize the ion migration (Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Video 1).” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1400)

“As time passes, an obvious PL quenching from the reference film is observed and it worsens rapidly. The PL quenching is attributed to the destroyed stoichiometry and/or structure of the crystals due to pronounced migration of charged defects in the reference film31. By contrast, the bright PL signal of the film incorporated with Nd3+ remains unchanged even after applying the bias voltage for 10 minutes, indicating that the migration of charged defects is suppressed by the addition of 0.08% Nd3+.” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1400)

“TOF-SIMS data confirm that the Nd3+ ion itself did not migrate during the operational stability test (Supplementary Fig. 17), which is consistent with the large energy barrier of the interstitial Nd3+ migration confirmed by DFT simulations (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26).” (Zhao et al., 2022, p. 1401)

For my Literature review 2023/03